Over the past years, the international portfolios of State-owned investment funds, known as Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs), have gained momentum. The SWFs’ foreign investments have attracted remarkable attention, both in the US and in Europe, due to a main question:

“are the SWFs a threat to recipient countries related to their national sovereignty and security?”

Making this question does not represent the best approach for understanding the Sovereign Wealth Funds universe. It needs, instead, to focus on some other -more fundamental- questions, such as:

(1) why the SWF is created by a Government;

(2) what their goals are;

(3) how the Government manages these funds.

Give sense to a “political approach” to the SWFs’ international investments is misguiding, since, in the long term – and often also in the short term -, the negative costs for the recipient States could be less than the positive benefits of the SWFs investments.

The dominant conception, that the State-investors are in pursuit of political power over other States, is unjustified. Also the assertion that SWFs are primarily used for balance of payments adjustments is unsound. Using a SWF, a Government act as investor in order to increase the value of their assets.

The global financial crisis brought back the State-investor on the markets. The activity of a State as a private investor is to be attributed to:

(A) the -generally widespread- funding shortage for investments;

(B) the negative aggregate effects of many policy-making mistakes (mostly in the regulatory function) and the resulting government action for preventing loss of political consensus;

(C) the fear of citizens for their future and their savings.

The State has revived for himself the role of “market player”, putting it beside its traditional role of “market regulator”. This new policy phase has been making easier by (1) an institutional investors’ weakness and (2) an ill-conceived role of the market and the State. The citizens, reversing the past “liberalist” (in a European sense) slogans, has started to call “more State and less market“, worrying less about the rules, and ignoring that the faults of the States are not less than those of the markets.

An important caveat about the “liberalist” concept. The meaning of the word “liberalism” diverges in different parts of the world. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, “In the United States, liberalism is associated with the welfare-state policies of the “New Deal”, starting with the Roosevelt Administration, whereas in Europe it is more commonly associated with a commitment to limited government and laissez-faire economic policies.”

Regardless of ideologies, it’s humanly understandable -but socially wrong-, that people nourish the hope to burden the community with their problem. John Fitzgerald Kennedy was right when he urged US citizens not to wonder what the State could do for them, but what they could do for the State. The distributive activity of a Government is always welcomed by the citizens since they hope to benefit from it without paying the cost.

Generally speaking, the market can offer new opportunities to those who can grasp them. The State tries to do the same but, because of its failures, sooner or later ends up to offer only mere assistance. Promising opportunities, indeed, the State feeds hopes of well-being in the citizens, whether they are poor, workers, unemployed, small or big businessmen, but by the end of the day its function turn to be a mere redistribution of resources and not a creation of new ones.

The Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) are the main political expression of the State-investor on the market. They operate as private entities but with public funds. It could be appropriate to consider that they are causing a reversal of the process started in the ‘70s, since they are the result of some real shortages, or mistakes, in processing the rules that governing global trade.

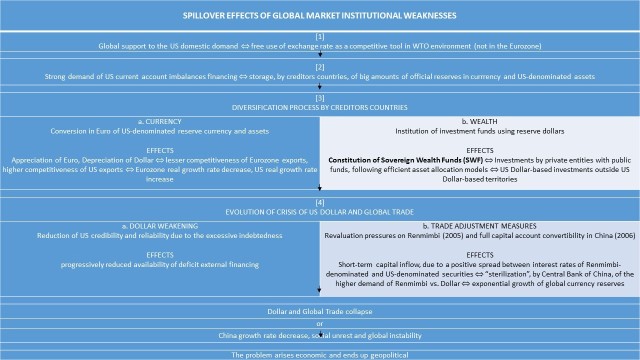

I can sum up in a scheme what I propose as the spillover effects of global market institutional weaknesses.

After the rejection of the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944, decided unilaterally by the United States in 1971, new monetary and currency rules did not follow. Global trade came under the control system of the WTO, the World Trade Organization, the institutional evolution of the GATT, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

After the rejection of the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944, decided unilaterally by the United States in 1971, new monetary and currency rules did not follow. Global trade came under the control system of the WTO, the World Trade Organization, the institutional evolution of the GATT, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

The WTO members could freely choose between “fixed” or “flexible” exchange rates for their national currency, unless they were not part of monetary agreements. This allowed some important countries with balance of payments surplus to choose between a “dirty floating” regime (i.e. with public, not systematic, intervention on the exchange rates) and a fixed exchange rate regime (with systematic intervention), while countries with balance of payments deficit could practice perfectly flexible exchange rates, whether the regime best suited to their interests.

In this way, countries with current account surpluses chose a regime of floating exchange, starting an accumulation of large reserves. This condition favored the emergence of (1) the unfair accumulation of official reserves and (2) the management of the external imbalances through a portfolio allocation of these reserves.

Moreover, the countries, holders of official reserves, could diversify their currency baskets also purchasing securities denominated in currencies different than those issued by them.

Thus, the exchange rate of a currency ended up to reflect the terms of trade, i.e. the rates at which the products of one country are exchanged for the products of the other, and tended to depend on monetary conditions and on the policies pursued by those countries, creators and users of official reserves. The economic policy of the United States and of the Eurozone, considered in their effects on the respective currencies, continued to set the tone of the monetary and financial global market, no longer alone yet. Also the exchange rate policies of China and other surplus countries would have had big relevance.

The trade-off between major current account imbalances and higher growth rates has made acceptable the geo-economics of the United States and China, laying the roots of the current crisis and increasing the shared responsibilities.

This structure of world trade has enabled the United States to see financed their deficits (therefore, their consumption) with the world savings, in particular from China. This “circular dynamic” has been stabilizing for both countries, for the value of their currencies, their trade balances, the purchasing power of their consumers, the inflationary pressures and interest rates in the United States, and, above all, for their respective cycles. Monetary policy in Beijing created a significant reserve in US securities.

The impressive trend called for a diversification of international reserves, as has fueled fears about a potential expansionary impact for the global monetary creation.

Countries holders of huge quantities of reserves started a process of currency diversification, opting for conversion to euro of US dollar-denominated securities. Then, they constituted Sovereign Wealth Funds as private legal entities that invest with state assets according to efficient asset allocation models. These tools have allowed the reinvestment of dollars in areas other than those where the US dollar is dominant.

The weakening of the dollar, as a result of this diversification process, caused, on one hand, a reduction of credibility and reliability of the US due to excessive borrowing, on the other hand, adjustment measures of trade which, in the particular case of the Washington-Beijing relationship, led to the revaluation of the Renmimbi/Yuan (21 July 2005) and the introduction of full convertibility on capital account in China (14 April 2006).

The consequences of this process, such as the reduced financing for the US current account deficit, the high risk of global trade collapse, as well as the social turmoil risk in China, linked to the domestic growth rate decline, showed how the Sovereign Wealth Funds issue was born economic but ends up geopolitical.

In the next post, we will talk about some practical definitions of SWFs.

This post was also published on LinkedIn.

DISCLAIMER: Any views or opinions presented here are solely those of the author and do not represent any official position of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

Brilliant post. The connection between geopolitical and economic angles can’t really be stressed enough. Looking forward to the follow-up post.

LikeLike

That’s very kind of you, Daniel.

LikeLike